- Home

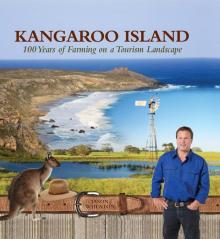

- Jason Wheaton

Kangaroo Island Page 7

Kangaroo Island Read online

Page 7

Stranraer primarily has two sheep enterprises. The merino breed is primarily for wool production whilst the crossbred is for lamb production. The above photo is of crossbred lambs.

The term crossbred ewe refers to the crossing of 2 breeds. The crossbred ewes that run on Stranraer are a cross between a Border Leister ram (English Breed) and a Merino ewe. The Border Leister has a wool micron of 30, while the Merino has a micron of 22 (on average). By crossing these breeds we have a highly fertile sheep with a wool micron of between 25-28. This type of wool does not command a premium price as its uses are limited, however in terms of lamb production the average lambing percentage is 120 versus 85-90 with the merino breed. The aim of lamb production is to achieve as many lambs as possible. In achieving the ideal prime lamb we then cross the crossbred ewe with a White Suffolk, which is the designated prime lamb sire.

The crossbred ewes have rams join them in early January. The rams are removed 6 weeks later. This allows for adequate cycling by the ewe to get into lamb. The gestation period of a ewe is 150 days and the lambing process commences in June. This lambing time is important to ensure that the ewe has adequate nutrition to support itself and the lamb. Ewes are scanned to determine twins and singles which assists in their management as twin bearing ewes require extra nutrition.

The lamb grows at approximately 300g per day on average through the winter and spring period. Lambs are weaned from their mother at 12 weeks allowing the ewe to recover and begin gaining weight again prior to the summer. The lambs can also graze on a higher quality feed to ensure weights are achieved.

The lambs are sold once they reach 40-50kg live weight depending on the domestic market requirements. There is also the option of growing the lambs out heavier and selling to the export market. The lambs reach the desired weight in late September/October. Lambs are loaded onto triple-decker trailers and transported to Adelaide for processing. Trailers can load approximately 400-450 lambs.

The price determined for the lambs is a per kilo price. Payment is made per kilo and the weight of each lamb is calculated and total net price paid. In the past, a lamb price was given by the stock agent as a live animal, nowadays a price is given based on carcass weight and a price per kilogram.

A price is also offered for the skin as these are used in producing products such as ugg boots in other countries.

80% of the lambs are sold this way, however there will be a portion of the lambs that will not get to the desired weight. These lambs may be shorn and kept for longer on lucerne, or will be sold to a feedlot for grain feeding.

The matching of these activities is very important. If the lambing date was later this would cause problems especially if the season finished earlier and the feed supply was reduced. It is important to ensure the ewe is also able to gain condition prior to the summer months to ensure that extra hand feeding with grain is not required as this can be costly.

Grass weed management is important for the lamb industry. Grass weeds such as brome grass, silver grass and barley grass all have the potential to impact on the lamb in regards to meat quality. The weeds have sharp seed heads that penetrate the pelt of the lamb and damage the meat. These weeds are managed through chemical use, grazing pressure to reduce the seed set and also by cutting hay prior to seed set. This stresses the importance of having the lambing and farm operations coincide with the rainfall pattern of the property and subsequent pasture growth.

Lambs of today tend to have less wool around the face due to improvements in breeding traits as opposed to lambs bred in the 1940s and 1950s. Less wool around the face and legs results in fewer grass seed issues and better ease of management with fewer fly strikes.

The crossbred ewes are shorn in Sept-Oct and cut approximately 4.5 kg per head. The wool is of a lesser quality than the merino. Shearers find the crossbreds easy to shear as they do not possess the skin wrinkles that the merino breed has.

The kelpie sheep dog has been an important employee at Stranraer over the last 100 years. The Australian kelpie originated from black collies imported from Scotland in the 19th century. Kelpies have the ability to run along sheep backs in order to push them forward. We have operated with some very good kelpies who are very loyal and able to understand whistle commands.

The merino production at Stranraer is using merino rams with merino ewes. There is no crossbreeding here. Merino production is very similar to the crossbred production in terms of management. This breeding system maintains the quality of wool produced.

Rams are selected based on wool traits and other parameters and are sourced from a stud in the mid north of South Australia.

Rams are placed with ewes at a rate of 2% at the end of January. Lambing for the merinos is in July. The process for merinos is not reliant on the lambs achieving a certain weight by a certain time but growth rates are important for the merino lamb to ensure size and wool quality later in life. Nutrition plays a vital role in this process.

Lambing percentages vary between the crossbred flock and the merino flock. Merino ewes achieve a 90% lambing percentage on average while the crossbred achieves a lambing percentage of 120-130%. Merino lambs are weaned from their mothers at 12-14 weeks. This, once again, allows time for the ewe to recover and to regain condition prior to the summer months. This process reduces the reliance on expensive summer feeding of cereal grain and hay.

CHAPTER 6 - Livestock & Hay Production

The working of the land in the early to mid 1900’s required the use of more than 50 Clydesdale draft horses. Just like a tractor needs oil and fuel today, it was a full time job maintaining the horses in peak condition. The now implement shed had a row of feeding troughs on the back wall that would interconnect with the chaff shed. It was a big part of the business, producing chaff to feed the working horses. Hay and chaff production for the property was an important aspect of the farm management.

Hay production in the early days involved placing the hay into sheafs, these would then be collected from the paddocks for transportation back to the shed. The process of producing a sheaf of hay is termed ‘binding.’ The picture below shows the binding process. The hay shed stored the hay and then the hay was placed in the chaff shed for processing into finer material for feeding to the horses. This was done in the long wooden feed boxes that lined the back area of the shed.

The binding process cuts the crop at the base and then wraps it, ties it with string to allow for easy pick up. This process also removes the grain which is included in the horse’s diet with the chaff. The sheaf was then wrapped in twine ready for collection and storage. Moisture management was also important to ensure it was not stacked wet and produced mould as a result.

Over time the mower was then developed. The mower cuts the grass which is then allowed to dry for a period of time. It is important to allow the hay to cure or dry before baling. After 10 -14 days, weather permitting, the hay is baled. If it does rain during the curing process then the hay may need raking to dry out the underside. In the 1930s more than 100 tonnes of hay was cut in this way every year to support the Clydesdale team of thirty horses.

From the binding of hay using the binder, hay production progressed to the use of tractors and crawlers with a machine called a ‘rectangular baler.’

This machine would pick up the hay with a rotating drum and metal-like fingers attached that would pick up the hay as the machine passed over the hay row. The hay would then go onto a conveyor belt and be compressed into a small rectangular bale, which was then wrapped with 2 pieces of string. The bale would then be dropped out the back of the machine for pickup.

The important thing with hay is to ensure that the hay is not baled wet as heat combustion can occur resulting in possible fire or damaged hay through mould.

The hay is then picked up from the paddock with a ground driven conveyor attached to the side of the truck. As the truck drove along the hay bale rows the conveyor belt would carry the hay bale up to the height of the tray where a labourer would stack it. Once th

e truck was full the truck would proceed to the hayshed for unloading.

Carting square hay bales, the photo above shows workers loading the rectangular bales into the hay shed. The bales are loaded off the truck onto a conveyor belt and elevated into the shed. This process requires a lot of hard work and manpower. These bales would weigh 40-50kg.

Hay production into the 21st century is a very similar process, however the process has become very mechanised. Round bales are now produced which weigh between 500 and 700kg. These are picked up from the paddock with a front end loader. Large rectangular bales are also manufactured.

This process is more efficient and reduces the likelihood of rain and water damage. The mowing process still uses the same principles but a machine called a ‘mower conditioner’ is used. This machine cuts and rolls the grass or crop which allows the material to dry more quickly and thus be baled sooner, again limiting the chance of weather damage.

Hay yields are very dependent on the season. In 2012 the still paddock was cut for hay. Pasture consisted of sub-clover and annual grasses. 90 rolls were processed over the 14 hectares, equating to approximately 3.2 tonnes to the hectare. Lucerne and annual grasses can yield higher numbers due to the amount of growth the lucerne can offer in the spring period. The long paddock was cut in 2012 yielding 130 rolls off 14 ha. This was a yield of 70 tonnes of hay, equating to 5.0 tonnes per hectare. The benefit of the lucerne pasture, which is a perennial, is that once hay is removed from the paddock the lucerne will regrow and offer grazing later in the summer, thus reducing feeding costs. This highlights the benefit of lucerne as a perennial plant in alkaline soils.

Pasture Production and Livestock Management

The basis of the pastures at Stranraer is sub-clover, perennial and annual grasses and lucerne. Sub-clovers are annual plants that germinate on the opening rains in April/May. If managed correctly they will flower and set seed to allow for continued production year after year. These types of sub-clover are highly palatable, digestible and high in protein. The aim of the perennial and annual grasses is to counteract the sub-clover’s high protein and energy and to provide a level of roughage for the diet.

Subterranean clover and various species of medic were introduced to South Australia as early as the 1870s from Mediterranean countries. These species spread throughout the cropping areas and grazing areas of South Australia. Subterranean clovers are annual species which tend to be hard seeded allowing seeds to set at the end of spring (September-December) evade the summer dry period and germinate in the next autumn. The introduction of superphosphate to Kangaroo Island revolutionised this species and its value to agricultural production. This species operates like lucerne as a legume plant and is able to draw in nitrogenous air and the plant is able to convert this nitrogen through its root nodulation system into available nitrogen.

Perennial grasses such as phalaris, which is the dominant grass on the hummocks, provide feed through the summer when rain events occur. Phalaris must be grazed cautiously as phalaris staggers can occur which has toxins impacting on the immune system of the sheep. The nutrition of the soil is very important in maintaining high quality feed for grazing livestock.

The soil pH of Stranraer ranges from 6-9. The highly alkaline soil suits lucerne production. New Lucerne is planted in August as the soil temperature increases, improving germination. The lucerne varieties are summer active providing high protein feed through the summer months. This reduces the reliance on grain and other feed stuffs such as hay which are expensive through the summer months. Lucerne is high in protein at 12%, which is excellent for maintaining the weight of breeding ewes prior to mating. Lambs that do not reach the desired weight may be carried through the summer months and grazed on lucerne post shearing to get them to the 45-50kg live weight. It is important that when grazing lucerne ,due to the high protein content, that roughage such as hay is also provided to prevent a condition called ‘Red Gut’ where the high protein diet irritates the lining of the ruminant’s stomach.

In planting lucerne other plant species such as perennial ryegrass and chicory, which is a brassica plant, are incorporated to provide this roughage.

A technique described as pasture cropping has also been implemented recently where cereal crops have been sown into the established lucerne pastures. These crops such as barley, wheat and oats can then be cut for hay or harvested. The cereal crop can be sown at the break of the season, May or June, and then be harvested in December. The dormancy phase of the lucerne operates through this period so there are no competition issues. Once the grain is harvested the lucerne then will be well and truly out of the dormancy phase and be able to provide stock feed. Weed control can be challenging especially in the control of broadleaf weeds such as capeweed as the chemicals used can impact on the lucerne also. The benefits of this system are:

Soil is covered at all times reducing the erosion by wind and water

Nitrogen can be supplied via the nodulation process of the lucerne, thus reducing fertiliser requirements

The ability to continually have land in production supports the grazing system.

Lucerne is sometimes cut for hay production and is seeded at 7kg/ha. A typical stand of lucerne will survive for 5-8 years if managed correctly from a grazing point of view. Over-grazing will result in the lucerne requiring re-seeding sooner. The aim is to use the no till process to limit the impact on soil structure, with fertilisers applied with the seed to encourage germination. Rhizobia and lime are applied to the seed to assist in nitrogen fixation and nodulation.

Lucerne as a perennial plant has a natural process of nitrogen fixation. This mean the plant has the ability to draw nitrogen from the air and convert it into a useable plant form. What the plant does not use is then released into the soil for other plants to use. This is a unique process and reduces the nitrogen required to be applied in the form of fertilisers and benefits the farmer in cost savings.

If you were to remove a lucerne plant from the soil, you will notice nodules on the roots. The more nodules that are present the more nitrogen fixation is occurring. Rhizobia is the bacteria that assists this process. Australian soils are naturally low in rhizobia.

The management of grazing of lucerne ensures its longevity. The paddocks at Stranraer are rotationally grazed to ensure the plants recover from grazing and that plant populations are maintained over time.

The important key to sheep management is to match feed supply with the stocking rate. Feed supply being a reflection of the rainfall. Stranraer feed supply peaks in the July-October period which reflects the stocking rate. October is our highest stocked month, with most lambs sold in this month. Feed demand is high in this month as lambs reach their peak weight (50-60kg live weight) and ewes return to good post lambing condition.

The pasture curve shows the typical growth of pasture over a twelve month period. Phase 1 is January to April, Phase 2 is May to August and Phase 3 is September to December.

Phase 1 is important for our ewes in regards to maintaining body weight over the mating period and into the initial stages of pregnancy. This area of farm production involves supplementary feeding with grain and hay to provide energy and protein to sheep as the paddock feed is minimal and of poor quality as this is the end of the summer period.

Phase 2 - Opening rains for the season on average occur in the April–May period. This allows the initial germination of paddock feed. Due to the warm soil temperature the early germination is rapid. The initial germination is of high digestibility and protein however, the quantity is lacking so supplementary feeding may continue into this period. Lambing commences in June and July and at this stage of the year there is adequate feed in the paddocks to support the new lambs and ewes. Supplementary feeding is not occurring at this point. The animal husbandry for the sheep occurs in this phase, lamb marking (tail docking) and worm control.

Phase 3 – Known as the spring period is a time of excess paddock feed that is high in protein, digestibility and energy. At th

is point the lambs are growing quickly and Stranraer is at its maximum with stocking pressure. The important area of management is to match the stock demand to the supply of feed. As stage 3 completes, the summer commences and it is important to have the majority of the prime lambs sold as the feed is in decline and not able to support the number of stock that were present in the early stages of this phase.

Pasture curve and sheep management calendar

January - Feeding to maintain ewe body weights, rams put out for breeding (6 weeks)

February - Feeding to maintain body weights, hay & grain feeding, summer worm drench

March - Feeding to maintain body weight, rams removed from flock

April - Feeding to maintain body weight, hay & grain feeding

May - Crutching all sheep prior to lambing (removing wool from backside of sheep for flystrike prevention)

June - Vaccinating ewes with a 6 in 1 vaccine, + B12 cobalt injection

July - Lambing commences (crossbred ewes)

August - Lambing (merino ewes), lamb marking (remove tails and castration of males), vaccinations of lambs and worm drench for ewes, tagging also for property identification

September - Hay cutting and baling, crutching of all ewes. This done prior to shearing removes all stained wool, which can contaminate quality wool, and allows for easier classing

October - Shearing of all ewes and crutching of all lambs to prevent flystrikes, selling of best prime lambs, live weight required by market is 42-48kg

November - Continue to sell prime lambs, shearing of merino lambs (wethers and ewes) prior to summer. This prevents flystrike possibilities and grass seeds invading wool over the summer

Kangaroo Island

Kangaroo Island